Why Does Genocide Still Happen?

Why Does Genocide Still Happen? The Lessons I Learned at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Sydney Kakuk December 23, 2022

When I was in middle school, my mother gave me a copy of the Diary of Anne Frank. I remember struggling to understand the twisted plot and instead found myself tracing the edges of a red, silken bookmark. I thought it was a romance novel at first. I imagined myself as Anne; my then crush, Peter. A hopeless romantic, I dove into the pages consuming each word with excitement. Yet, I emerged battered and brittle. I realized I was not interested in the love story but in the events that led to this atrocity. I remember being the same age as Anne Frank, yet instead of survival, my mind was occupied by sports, boys, and friends. A question formed in my mind. Why does genocide happen?

Kakuk holding the two bachelor’s degrees she earned after graduating from the University of Minnesota in the fall of 2021.

As I grew older, I found myself drawn to art representing man’s duality: a beautiful, cruel species. Starving for answers, I inhaled classical art, music, and literature that reflected the struggle to survive under the thumb of authoritarian regimes and oppressive systems. I gorged upon books like Kite Runner, The Glass Castle, All Quiet on the Western Front, Night, and Animal Farm, to name a few. I remember first learning about the Uighurs in Xingang and watching Hotel Rwanda – becoming horrified to find out there has been more than one mass genocide in recent history. In my freshman year of high school, I took a life-changing trip to South Africa. There, I saw the cleavages left from the apartheid. Brilliant mansions overlooked sprawling slums – remnants from ethnic zoning laws carved into the earth. Patterns of bullet holes speckled the walls and pews of traditionally black churches used for illegal political discussions. Life-sized photographs of parents carrying wounded children stoically stood in the squares; a moment of horror immortalized. When I stood at the gate of Nelson Mandela’s cell on Robben Island, I wondered again: Why does genocide happen?

In my senior year of high school, I began training classically as an operatic soprano. In this space, I gravitated toward a new question: Why does genocide still happen? I decided to go to college to study Vocal Performance. I was eager to spread messages through song. I wanted to carry on the stories of those like Anne Frank. I wanted to be a vessel for the silenced voices; I wanted to be a kaleidoscope of the human condition and reflect a multitude of emotions. I wanted to feel their pain, their hope, their joy. I wanted to live through them. I remember reveling in Poulenc’s “C.” and Gurney’s “Sleep” while intensely studying the effect of censorship and political violence on musicians such as Prokofiev, Messiaen, Schoenberg, and more. I remember softly crying during my choir’s performance of Stephen Paulus’ “To Be Certain of the Dawn,” a Holocaust oratorio.

Kakuk holding the two bachelor’s degrees she earned after graduating from the University of Minnesota in the fall of 2021.

I remember squirming in my chair during my music history course while being lectured on Krzysztof Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.” This piece sparked my interest in nuclear issues, as it commemorates the largest and most horrifying genocide in human history. Experiencing music in this way led me to seek a career in international security and peace. When beginning my second degree in political science at the University of Minnesota, I focused heavily on nuclear weapons policy and international relations, and security. This led me to pursue opportunities in the nuclear policy space and landed me at the Nuclear Threat Initiative for my fellowship. I have found I am incredibly interested in the human connection to these weapons of mass destruction, and I hope to marry music with policy to create bridges of understanding between people and nations. While music and nuclear policy seem distant from one another, they are tightly intertwined in my story. So far, I have worked on projects with a solid human element – such as evaluating the threat of domestic violent extremism on nuclear facilities. Moreover, I have dug deep into Russia’s war on Ukraine, evaluating nuclear risk and documenting escalatory rhetoric from the Russian government.

Naturally, I was filled with emotion entering the U.S. National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. My family and I had decided to visit over Thanksgiving weekend while we reunited after months apart. It felt like a full-circle moment in my life. I recently moved to the DMV from Minneapolis for the Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellowship. I was diving deep into my work in the third month of my fellowship at the Nuclear Threat Initiative. Now, I was with my mother in front of a life-sized photo of Anne Frank – two women who have inspired me to try to do good in the world. The golden glow of autumn sunshine tenderly caressed the stoic staircase from which I descended. Landing gingerly upon the museum floor, my eyes were drawn upward to the light pouring through sparkling glass panels, nestled comfortably in the embrace of stark metal beams. The sun painted geometric patterns across parallel lines of earthen brick. There, a sign hung. “This museum is not an answer. It is a question.” And it was the same question I had been asking for years.

Kakuk in front of the U.S. Capitol Building in December 2022.

As a first-time visitor, I was eager to see the stunning artifacts preserved from an era defined by monsters and martyrs. The dark hallways were curved like a winding stream – photos of those forgotten laid quietly upon their banks. Slowly, their smooth, stone-like faces were eclipsed by the bodies of impatient patrons. Off-balance, I hugged the wall as the hall swelled with people who were jockeying to see a glimmering pocket watch and a pair of silver spoons. Amid a pandemic, with hardly a mask in sight, a sick child coughed loudly as his father eagerly pushed him to the front of the crowd. Suddenly a phone rang out, “I’m good. How are you,” a person answered confidently.

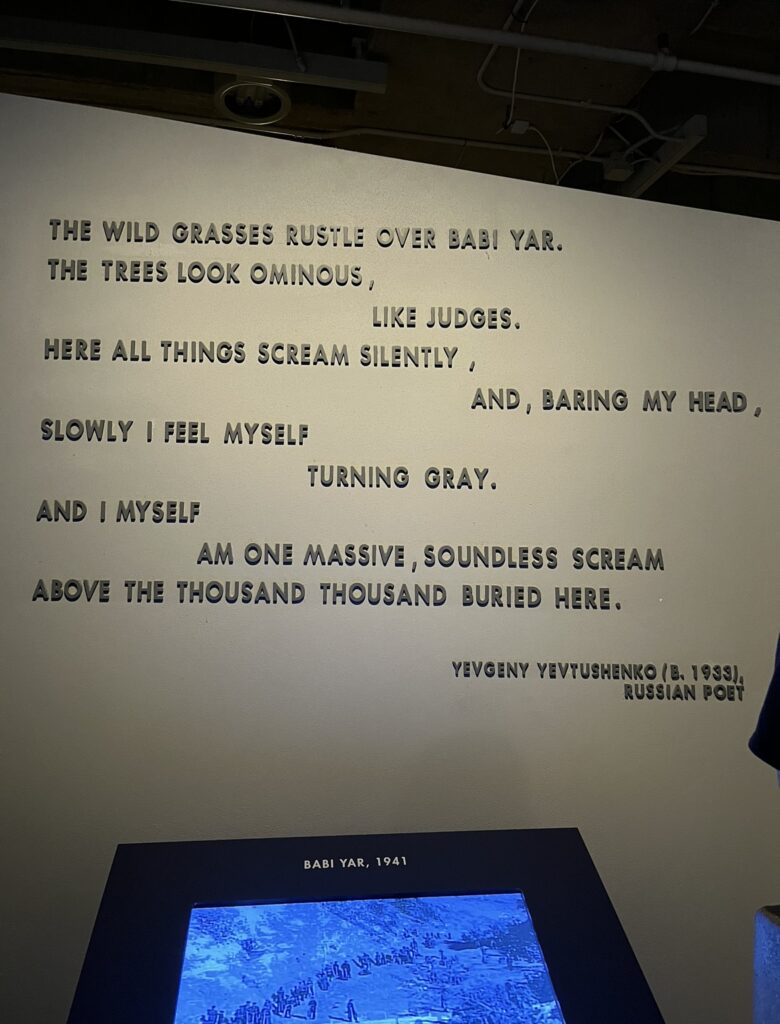

The photos of naked, beaten women were blanketed by casual conversation and an infant crying. A video screen behind a concrete partition boldly displayed the dismembered bodies of medical test subjects, yet a man was scrolling through TikTok. A young child laughed about the happenings of her friends at recess. A teen meandered through aimlessly; he was blinded by a broadcast of a soccer match taking place at the World Cup. “Too rad to be sad,” a gentlemen’s shirt read as he combed through the exhibit. I was astonished. Perhaps I am being dramatic, but the scene here was shockingly disrespectful and perpetrated by patrons who had chosen to spend their day at the museum. It is a place that was made to remember, yet millions of victims remain forgotten. A hollow blue screen brought me back to reality, back to 2022. The footage from the 1940s showed a decomposing corpse in a Ukrainian river. I was reminded of photo galleries posted by @donbas.frontliner on Instagram just a few days before. A poem over a photo of Babi Yar read, “And I myself am one massive, soundless scream above the thousand thousand buried here.” I thought of the recently exhumed mass graves in Kharkiv, Kherson, and the Donbas. I thought of the thousands of Ukrainian children being captured by Russia and given to Russian families, unwittingly helping the state bury the children’s heritage and culture. “Never again,” the world said, yet here we are, reliving the horrors of the Holocaust, the Ukrainian steppe once again stained by red.

A poem featured in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

At the end of the permanent installation, there was a small exhibit devoted to the genocide occurring in Myanmar against the Muslim minority, the Rohingya. While the central part of the museum was buzzing, the Burma exhibition was nearly empty. In a photo, a young teen held a sign that read, “No Rohingya in our land.” My mind wandered back to the boy watching the World Cup; they seemed to be about the same age. Some may defend the soccer fan by saying he is merely a child and could be bored or uncomfortable. I looked at the black and white photo of the picketing boy; perhaps if children are not expected to internalize such lessons, they leave room for hate within their hearts. Stephen Paulus famously said of his oratorio “To Be Certain of the Dawn” that it was created “to help teach an important lesson: the prevention of future genocide is in the hands of today’s children.”

So, why does genocide still happen? The Holocaust Museum taught me that perhaps hate grows in the place of underdeveloped empathy. And unfortunately, my experience in the nuclear policy field has taught me that there is not much empathy in international relations and security. In a field that is supposed to be about protecting people, it seems that the security community often erases the human element in favor of numbers and figures. Numbers are numbing. Holocaust survivor Abel Herzberg said one of the most powerful quotes featured in the museum. “There were not six million Jews murdered; there was one murder, six million times.” Where numbers and figures fail, art, literature, and music invite people into the conversation – they make tragedy tangible. Traditionally, the relationship between art and policy is primarily seen in propaganda. Yet, the same power could be used as an educational experience rather than a coercive tool. Perhaps, the arts and humanities need to play a more significant role in international security to create better-informed policy. Perhaps, art is the fuel that keeps the human spirit alive – is that not the same goal as the international security community?

Sydney Kakuk is a Fall 2022 Scoville Fellow with the Nuclear Threat Initiative.