Seeking Out Serendipity, Taking My Background With Me

Ending up in Asia for three years was never in the cards, but looking back, it kind of makes sense. A left-leaning vegetarian from Versailles, Kentucky, I half-jokingly tell a story that growing up in Versailles [vur-sails] and growing on a street adjacent to Marsailles Road [mar-sails] serves as my first foray into international relations. The real inspiration for this journey, however arises from the fact that much of my coming-of-age and current identity is steeped in a strange confluence of being very much rooted and linear, but also feeling slightly out-of-place. But it’s a bit weirder than that.

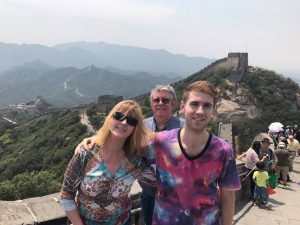

I have awesome parents. My father—an Eastern Kentuckian from Beauty, KY—met my mother while square dancing at the Air Force base he was stationed at in the Netherlands. My father comes from the quintessential Kentucky family: living on a farm, 9 siblings, livestock, and their closest neighbor living more than a mile away. My mother grew up in The Hague, referred to as the “international city of peace and justice” or the “legal capital of the world.” My mother comes from a family of shipbuilders that used to own a port, but they gave that up and then owned a flower shop in Delft. Her maiden name is literally “of the beer and bread.” So, those two worlds came together and raised my brother and me in Kentucky, in a town where people go on country dips, drink Woodford Reserve bourbon, and sometimes drive tractors to school. But we were also close to Lexington, which I would contend counts as a pretty big city. That was my understanding of a city until I was 20.

At Centre College, a small liberal arts school in Kentucky, I started out thinking I would pursue math. My parents had pushed my brother and me intensively to be math focused; I competed in MathCounts, was the math guy on my high school academic team, and almost left high school after my sophomore year to enter a math and science academy at Western Kentucky University, where I would have graduated college two years early. But I ended up pivoting away from it –- I just couldn’t muster the inspiration to work hard on problem sets. I considered five or six different majors for a few semesters, and I wasn’t really jazzed about anything particular, aside from Mandarin and Asian Studies courses.

Centre College was incredible in myriad ways, but probably more than anything was the commitment to studying abroad, close student-teacher relationships, and the tight-knit community. I didn’t realize it at the time, but in hindsight I can locate two central reasons for my selective diligence: the people I wanted to work with and the feeling that the work imparted. I really admired the work and lifestyle of my future adviser, Kyle Anderson, and honestly had not felt challenged until I started trying to learn Mandarin.

Mandarin is really hard. I was both tonally-challenged and hard-headed, which gave rise to a student that could and would memorize every vocab list and every sample dialogue in a textbook, but would struggle to recreate tones or particularly foreign phonemes (for the Pinyin-aware: rou vs. ruo; ce vs. ze). I really wanted to be good at the language, but most of my language acquisition came through rote memorization. Dr. Anderson planted the idea that I could springboard my language acquisition by studying in an intensive program abroad, and the rest is history.

I attended the International Chinese Language Program at National Taiwan University in Taipei after my sophomore year, and I was both overwhelmed and over-ecstatic. I was so much worse at the language than my peers there and felt tremendously pressured to catch up. At the same time, in Taipei I rode public transit for the first time, I lived on my own for the first time, so many firsts. There’s a Facebook picture of me standing on a bus on the way to the National Palace Museum which is the first time I rode a public bus that wasn’t affiliated with public school. Living on my own (with an incredibly patient roommate) abroad was a challenge in itself. I had never been in a major metropolitan city before Taipei, much less lived in one. But being out-of-place and uncomfortable has served as the lynchpin for my trying to fit in, assimilate, and learn the language.

But one summer in Taipei was nowhere near sufficient to bring my language ability to functional use. I was fortunate to spend the following semester in Shanghai studying at Tongji University and then the summer after that in Hangzhou at Zhejiang University of Technology, both opportunities focused on intensive language training. In both Shanghai and Hangzhou I would study the language formally during the day, and then I would go on runs most nights and get lost intentionally, forcing myself to talk to people on the street to find my way back, extending conversations as long as the other party was willing.

I graduated undergrad with a pretty strong language ability, scoring an Advanced High level on my Department of Defense Oral Proficiency Interview after my junior summer. But, in my blind pursuit of language acquisition, I had not really thought of an end goal -– so I naturally went to more school! I pursued my MA at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies (HNC), where I lived in Nanjing, China for two years, attended a majority of my international relations courses in Mandarin, and wrote a graduate thesis in Mandarin. This is where the story gets a lot less linear. When choosing a thesis topic and thinking about potential careers afterwards, I had no idea what would have an actual value add.

The problem was that I had spent so much time in the classroom that I had no real-world experience. For that reason, I made it a goal while at the HNC to gain formal work experience with as many different sectors as possible. I worked with a start-up NGO in DC focused on using labor mobility as a sustainable method for refugee resettlement, consulted with the Chinese branch of a Big 4 firm, provided foreign policy analysis for the State Department, and ran the China bureau of Johns Hopkins’ graduate newspaper. All of these experiences were incredibly different, and although they were only internships, I believe that having these opportunities afforded me an ability to venture out of my professional comfort zone and decide what environment and what kind of work was right for me.

It was my work with refugee resettlement in DC and a few impactful friendships that inspired my academic and career interests. That internship led me down a rabbit-hole where I explored the linkages between China and the Syrian civil war and found that there was a really important but scantly covered relationship between the two. This relationship served as the primary angle for my Master’s thesis, where I analyzed China’s voting trends in the United Nations Security Council and assessed Beijing’s strategy for humanitarian intervention in Syria and Libya.

Although I am currently engaged in similar research as a Scoville Fellow –- looking at China’s changing role in international conflict and international ceasefire mediation -– I never set out with this objective. Finding out what interests me and to what work I want to commit myself has grown out of a syncretism of my parents and upbringing, redefining myself online, exploring disparate paths through education, and always trying to create more options. And having all of these component aspects undergirding my experiences has been predicated on both investing in other people and having other people invest in me. I am incredibly thankful for the support of my family, teachers, friends, mentors, and so on for helping me stay on course during a pretty unconventional journey, but it goes both ways.

My motivation for the work I do now is centered on liaising all of these different, and sometimes oppositional, groups and persons that have lent to my personhood. Many of my friends from Kentucky are not following issues like the U.S.-China soybean tariff or the conflict in Eastern Ghouta, and similarly, friends from China have no point of reference for what is happening or how someone thinks in Versailles, KY.

It’s interesting, though, that my original motivation for running with the China thing for as long as I have was because it was different -– it was a means to leave the bubble that I thought I had become trapped in. But after leaving Kentucky, I came to feel so much more connected to it. While I’ve always existed in a weird in-and-out relationship with my roots, that part of me has shined much more resiliently when juxtaposed with those that grew up connected to big cities and/or a sense of internationalism.

It’s also so important to have more people bridging these seemingly incongruous people groups. In a time where those in the policy world try to analyze (pejoratively and disingenuously) the way in which the rural, disenchanted population acts and vice-versa those that are disconnected from policy see suit-adorning humans in Washington as snakes-in-the-grass, there are very few people that are trying to foster earnest conversation and understanding between both sides. This charge came to light problematically with the rise of the novel Hillbilly Elegy; J. D. Vance’s narrative more so provided a lens, as someone who distanced himself from his rural upbringing, for which those that have never really engaged with non-city people to assess and characterize non-city people. This doesn’t help the sides come together -– we need inclusivity and equitable conversation.

And that’s where I hope to come in. Creating avenues to facilitate conversation about hard topics that people aren’t talking about in ways that allow divergent people groups to equally wrestle with the subject matter. While writing my graduate thesis I came across a Kofi Annan quote that serves as a signpost for everything I do now: “Education is, quite simply, peace-building by another name. It is the most effective form of defense spending there is.” This education needs to be inclusive, informal, and challenging. I’m committed to doing my part by bringing the China angle and my Kentucky background with me into everything I do and fostering communication and debate among those groups, but I more so aspire to plant a seed of fostering dialogue in my friends and peers, so that they, too, will take with them their background and help to bolster a more interconnected culture of conversation.

Logan Pauley is a Spring 2018 Scoville Fellow at the Stimson Center